Welcome to the website of Liz Calvert Smith, where you will be able to find out more about the work of a food historian.

Welcome

Featured

Posted in General

Posted in General

Welcome to the website of Liz Calvert Smith, where you will be able to find out more about the work of a food historian.

13 Wednesday Feb 2013

Posted in Blog, Food adulteration, Magazine Articles

Dining was a very risky business in the nineteenth century, you could never be quite sure exactly what you were eating. Of course, the adulteration of food was nothing new; it had probably existed in some form or another as long as people had sold or bartered food. In fourteenth century London, for example, people were fined for selling, amongst other things, stale fish, stinking pig meat and wooden nutmegs. There were laws to deal with deception, but any admixtures were difficult to detect before scientific testing, which only became possible some five hundred years later. Medieval testing was along the lines of sprinkling powdered unicorn’s horn into wine to test for poison; if present, it would change the colour.

The scale of the problem increased dramatically in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the rapid growth of the towns. Supplying enough food to meet the demand was a problem, so the obvious answer to many traders was to cheat. Bulk was added to basic foodstuffs, with inferior substances: mustard powder was mixed with wheat flour and turmeric, cheese was coloured with red lead, coffee was found to contain burnt beans, burnt sugar, acorns and mangel-wurzel. Flour, perhaps the most important staple, was adulterated with plaster of Paris, pipeclay and even ground up bones. It was claimed in an anonymous pamphlet of 1757 that:

“The charnel houses of the dead are raked to give filthiness to the food of the living.”

This was never proved with certainty. What was well known, and accepted by some, was the use of mineral salt called alum to whiten the bread and improve the volume. Alum is an astringent, and whilst not especially harmful, it caused serious digestive problems in those whose diet consisted of very little other than bread.

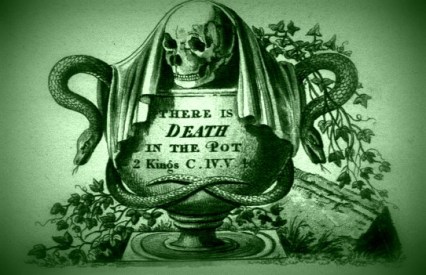

The public was first alerted to the state of their food by the German-born Frederick Accum, a chemist in London, whose work, A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons caused a storm when it was first published in 1820. It sold out in a month and ran through four editions in two years. Accum took the bold step of naming those who had defrauded their customers and was eventually hounded out of the country by the enemies he created. It was to be another fifty years before effective legislation was introduced, meanwhile, people were made aware of the dangers they faced from their apparently innocuous shopping. Household and cookery books gave details of how to look for unwanted additives in food. Bread could be tested for alum by sticking a hot knife into a one-day-old loaf; if the mineral was present, particles of it would stick to the blade and it would smell “peculiar”. Bread could also be tested for the presence of chalk by simmering a slice for two or three hours in water, leaving it to settle, and then checking to see if there were any whitish deposits in the water. There were dangers everywhere and traders went to very elaborate lengths to sell food which was “past its sell-by date”. Sides of beef, amazingly, sometimes had new fat put on them which was polished with cloths to make it look fresh. Poor quality wine may have been mixed with sugar or lead to improve its character; the test for this was long and complicated. Dr Paris’s method was as follows:

“Expose equal parts of sulphur and powdered oyster shells to a white heat for fifteen minutes and when cold add an equal quantity of cream of tartar. These are to be put into a strong bottle with common water to boil for an hour, and the solution is to be decanted afterwards into one ounce phials, adding twenty drops of muriatic (hydrochloric) acid to each. This liquid will precipitate the least quantity of lead from wines in a very sensible black precipitate”

The housewife obviously had to add chemistry to her already long list of skills. One imagines that by the time she had finished testing and found most results positive, she had probably lost her appetite anyway.

One source calculated that two-thirds of all foodstuffs sold in the mid-nineteenth century were adulterated in some way. Henry Mayhew quotes a leading grocer in his major work, London Labour & The London Poor,as saying that he could mention twenty shops in the city where one could be sure the coffee sold was adulterated. He then cites this as:

“..convincing proof of the general dishonesty of grocers.”

Pies are really much too unpleasant to consider. One pieman told Henry Mayhew that when he visited public houses to sell his wares:

“..people would often begin crying, ‘Mee-yow’ or “Bow-wow-wow’ at me, but there’s nothing of that kind now. Meat, you see, is so cheap.”

People must have needed very suspicious natures to shop successfully. For example, it would seem that fish was obviously fresh or stale, but tricks could be practised here too. One Manchester chemist told how fish sellers would come into his shop and buy red lead to paint their unsold fishes’ gills to make them look fresh. Others used pipes to inflate old, sunken cod fish. According to the cook, Eliza Acton, one could tell when prawns and shrimps were fresh by:

“..the vivacity of their leaps.”

People went to extraordinary lengths to cheat. Old oranges were boiled to “freshen” them up and dried coconuts were drilled, filled with water, and resealed with wax. Tea was perhaps the greatest scandal of all. Used leaves were dried, coloured with copper or black lead and resold, perhaps more than once. Punch magazine imagined a tea-loving spinster who:

“..proud of the cheery loveliness of her fireplace, would acknowledge a spasm of horror could she know that the polish of their own stove and the bloom of her own black tea were of one and the same black lead.”

Perhaps the most surprising feature of all this is the immense scale on which adulteration was practised. It was not until the Food & Drugs Act of 1872 that analysts were appointed throughout the country and food adulterers began to be prosecuted.

First published in Period House magazine, under the title “What’s Your Poison?”, in the October 1996 issue. © Liz Calvert Smith

25 Tuesday Sep 2012

Posted in Blog, Georgians, Liz Calvert Smith, Magazine Articles

Leg of mutton with oysters, ducks á la mode, transparent pudding covered with a silver web; it is hard to believe that these elegant dishes were produced in the Georgian kitchen, where cooking methods had scarcely changed for centuries. Most of the food was cooked over a large open fire; hot, dangerous and difficult to manage as, no doubt, was the cook by the time she had finished. Meat was roasted on a spit fitted onto the front of the grate, turned mechanically by a clockwork spitjack, and basted constantly. Maintenance of the fire at just the right hear was of prime importance, and the cook was also instructed to “observe, in frosty weather your beef will take half an hour longer.” It is interesting to note that this is true roasting, whereas meat cooked in the oven is really baked meat.

Boiling was the other usual method of cooking. Pans were large and heavy; they had to be for recipes like Scotch barley broth which began, “take a leg of beef chopped and four gallons of water…” Cooks had to be strong as well as heat resistant. Perhaps surprisingly, most of the authors of cookery books of this period stress the need for ‘delicate cleanliness’. Spits and pans were to be scoured with sand and water, while oil and brick dust were not to be used for fear of tainting the meat.

In large homes, stoves built of brick had been in use since the end of the 17th century. They had small firebaskets set into the top, were fuelled by charcoal, and provided a gentle heat for preparing sauces and delicate dishes. However, the fumes could be unpleasant. In his diary of 1800, Parson Woodforde described how his niece became giddy by standing too long over the charcoal stove making jam. Of course, ovens were in use as well. They were made of brick, domed or arch-shaped, with a door of iron or oak, but they had to be ‘fired’ or heated before they could be used. A fire was lit on the floor of the oven and allowed to burn for up to two hours. This was then swept out, the door was shut tight and the oven left for ‘a little while’ for the heat to be evenly distributed into the brick walls. I have tried this a number of times, and found that the only way to judge when the temperature is right is by experience. So much depends on the type of wood used in the firing. Bread was baked first, and then pies in the ‘falling heat’. If the oven was well managed, the whole range of decreasing temperatures could be utilised, the coolest being used for making puffs (now called meringues) or even for drying herbs of feathers.

In sharp contrast to the heat and bustle of the kitchen, the dining or eating room, as it was originally known, was a haven of taste and elegance.

Dining could be a very pleasant experience in Georgian times. Tables of the rich and discerning were spread with numerous dishes; meat, game and various pies, potted meats, jellies, creams, pickles and sweetmeats. It seems that food became something of an obsession. Poems of praise were written, especially about meat. Goldsmith wrote lovingly, in The Haunch Of Venison:

“The haunch was a picture for painters to study,

The fat was so white, the lean was so ruddy…”

Dean Swift wrote in a similar vein in praise of mutton, whilst the Rev. Sydney Smith expressed his feelings in a poetic recipe for mayonnaise, concluding:

“Serenely full, the epicure may say,

Fate cannot harm me – I have dined today.”

For the fortunate , food was abundant, servants were plentiful and cookery was developing into a fine art. A seemingly endless stream of books on the subject was published during the century and, despite Dr Johnson saying, “Women can spin very well, but they cannot write a good book of cookery,” most of the bestselling books were written by women.

The dinner hour had gradually moved from around noon at the beginning of the century, to early evening by the end of it. This is only a generalisation, as times changed more slowly in country areas where old habits died harder.

The choice of ingredients increased steadily throughout the century; largely because of improvements in agriculture and roads. Vegetables were no longer frowned upon by medical men, and soon formed part of the daily diet of both rich and poor, the latter eating mainly roots and greens. Exotic fruits were much sought after and those who could afford them had orangeries built, or grew pineapples in specially constructed pineries with ‘lofty stoves’ or ‘fluid pits’. It was considered particularly stylish to serve fruit and vegetables out of their usual seasons. Richard Bradley, a cook, mentioned this when he wrote “the pride of the gardeners about London chiefly consists in the production of melons and cucumbers at times before or after their natural season.” We take this for granted now.

It was becoming very fashionable to employ a French chef, but they were deeply resented by many people who felt that the ‘roast beef of old England’ was the proper food for Englishmen. Many cookery books of the period gave French recipes, but none more grudgingly than Hannah Glasse in 1747. After long and complicated instructions as to the French way of dressing partridges, she says, “This dish I do not recommend, for it is an odd jumble of trash…and the partridge will come to a fine penny.”

Although often quoted, it is unlikely that anyone ever began a recipe with the instruction “First catch your hare…” Originally, it may have been “first case (or skin) your hare,” but whatever the truth of it, 18th century cooks were certainly much less squeamish then than their descendants were to become.

If you would like to try a Georgian dinner party, the following recipe books should help:

23 Sunday Sep 2012

Posted in Blog, Liz Calvert Smith

I have a history degree and I’d always enjoyed cooking, so I thought it was a great way to combine the two. Also, you can access so much social history through finding out how people’s culture and social standing affected how and what they ate – after all, food is the one thing we all have in common, wherever we live, whoever we are.

Where to start! So many things – it’s such a rich, endless subject with so many different avenues to explore. Social history, medicine, geography, literature and many more. The research, meeting such interesting people, seeing some wonderful places – beautiful stately homes, museums and different parts of the world.

I’m planning to put a lot more photos of work I’ve done in the past, alongside articles I’ve written for magazines on a variety of subjects including ice houses, tea, pleasure gardens and remedies. Also, I’ll write regularly about different aspects of food or food history – seasonal, regional, cultural – why not suggest something you’d like to know more about? You can contact me on liz@edible-history.com or find me on Facebook or Twitter.

Syon House 18th century banquet, by Liz Calvert Smith